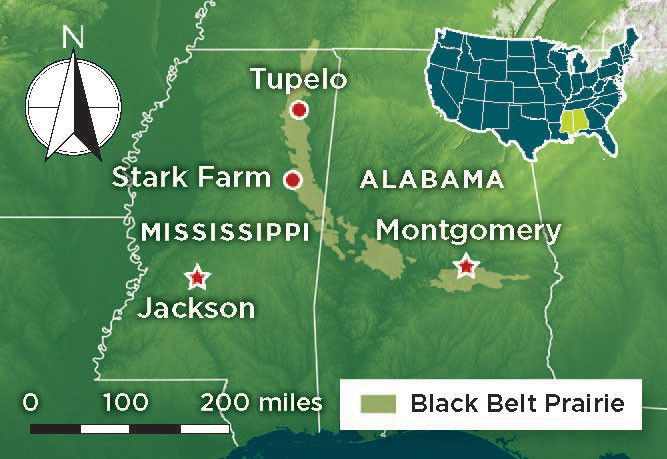

The Blackland Prairie is a crescent-shaped swath of land extending from central Alabama into northeast Mississippi. Its fertile landscape is dotted with farms, cattle ranches, and the occasional commercial or industrial complex. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the region was one of the United States’ major cotton producers. However, centuries before, it was a vast grassland and home to the Chickasaw Nation, whose heartland was centered around the modern-day city of Tupelo, Mississippi.

The Blackland Prairie is a crescent-shaped swath of land extending from central Alabama into northeast Mississippi. Its fertile landscape is dotted with farms, cattle ranches, and the occasional commercial or industrial complex. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the region was one of the United States’ major cotton producers. However, centuries before, it was a vast grassland and home to the Chickasaw Nation, whose heartland was centered around the modern-day city of Tupelo, Mississippi.

Today, a scattering of archaeological sites in the region, including ancient villages, burials, and battlefields, attest to the Chickasaw presence in the Blackland Prairie, but there are no longer any Chickasaw there. The tribe was forcibly removed from its homeland in 1837 and resettled 500 miles away in what is now Oklahoma. Recently, the Chickasaw have partnered with archaeologists from a number of academic institutions in an effort to identify heritage sites in their native Mississippi. “Preserving and reconnecting with our historical cultural heritage is critical for the continuance of a strong Chickasaw cultural identity,” says Brad Lieb, the Chickasaw Nation’s director of Chickasaw archaeology.

Today, a scattering of archaeological sites in the region, including ancient villages, burials, and battlefields, attest to the Chickasaw presence in the Blackland Prairie, but there are no longer any Chickasaw there. The tribe was forcibly removed from its homeland in 1837 and resettled 500 miles away in what is now Oklahoma. Recently, the Chickasaw have partnered with archaeologists from a number of academic institutions in an effort to identify heritage sites in their native Mississippi. “Preserving and reconnecting with our historical cultural heritage is critical for the continuance of a strong Chickasaw cultural identity,” says Brad Lieb, the Chickasaw Nation’s director of Chickasaw archaeology.

This research has enabled a new understanding of the Chickasaw’s traditional home and their long path through the American Southeast. It has also underscored their unique ways of navigating the age of European colonialism. In addition, recent excavations are providing clues to the whereabouts of Chikasha, one of the most historically important Chickasaw sites, and one that has eluded archaeologists for as long as archaeology has been an endeavor in this region. What took place at Chikasha was not only a watershed moment in Chickasaw history, but also a pivotal episode in the story of North America. Sixteenth-century Spanish accounts record that it was at Chikasha that the ancestors of today’s Chickasaw came face-to-face with Europeans—specifically with the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto—for the first time. This encounter ended in a brief but bloody skirmish, known as the Battle of Chikasha, during which the Native Americans launched a surprise attack on the Spanish, forcing them to flee in the middle of the night, abandoning stores of precious supplies that they desperately needed to sustain them on their march through the American South.

In 2014, archaeologists’ attention was drawn to a location in the Blackland Prairie outside Starkville, Mississippi, known as Stark Farm. The area had been surveyed by a cultural resource management firm after economic development plans were introduced. During the survey, archaeologists found Native American cultural material dating to the contact era, roughly 1450 to 1650. Around this same time, the Chickasaw Nation initiated an archaeological project to investigate ancestral sites in Mississippi in collaboration with the University of Florida, the University of Mississippi, Mississippi State University, and the University of South Carolina’s Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology. To give younger members of the Chickasaw Nation a close look at their deep history, they also founded the Chickasaw Explorers program, which provides an opportunity for Chickasaw college students to participate in archaeological fieldwork alongside faculty and students at universities in the Southeast. Stark Farm appeared to be an ideal place to start. “For most of the students, it’s the first time they have been able to return to the traditional Chickasaw homeland and it’s an emotional experience,” Lieb says.

The Chickasaw themselves had no written language. The Spanish referred to the Native people of this region as Chicaza or Chikasha. As was Spanish custom, they called the people, the region, the town, and the tribal leader, or minko, all Chikasha, which is today pronounced “Chickasaw.” The Chickasaw were part of the Mississippian culture that flourished in the Southeast between A.D. 900 and 1700. Chickasaw territory included northeast Mississippi, northwest Alabama, and western Tennessee. Archaeological evidence has indicated that while their eighteenth-century settlements were located around Tupelo, Mississippi, the Chickasaw had moved to this area from farther south in the Blackland Prairie, around Starkville. If this is true, the archaeological project at Stark Farm could provide the opportunity to uncover some of the earliest Chickasaw archaeological sites. “Initially, we weren’t focused on finding Chikasha,” says Charles Cobb, an archaeologist with the University of Florida and the Florida Museum of Natural History. “We mainly wanted to find a good sample of sites from the 1400s to 1700s that would allow us to model Chickasaw migration and settlement in the Blackland Prairie through time.”

The Chickasaw themselves had no written language. The Spanish referred to the Native people of this region as Chicaza or Chikasha. As was Spanish custom, they called the people, the region, the town, and the tribal leader, or minko, all Chikasha, which is today pronounced “Chickasaw.” The Chickasaw were part of the Mississippian culture that flourished in the Southeast between A.D. 900 and 1700. Chickasaw territory included northeast Mississippi, northwest Alabama, and western Tennessee. Archaeological evidence has indicated that while their eighteenth-century settlements were located around Tupelo, Mississippi, the Chickasaw had moved to this area from farther south in the Blackland Prairie, around Starkville. If this is true, the archaeological project at Stark Farm could provide the opportunity to uncover some of the earliest Chickasaw archaeological sites. “Initially, we weren’t focused on finding Chikasha,” says Charles Cobb, an archaeologist with the University of Florida and the Florida Museum of Natural History. “We mainly wanted to find a good sample of sites from the 1400s to 1700s that would allow us to model Chickasaw migration and settlement in the Blackland Prairie through time.”

The team surveyed and excavated a variety of sites at Stark Farm, and it soon became apparent from the cultural material—including pottery, lithics, and animal bones—and other features that Stark Farm had once been a significant Native American residential site dating to the precontact and early contact period. “Archaeological testing quickly revealed significant midden and architectural evidence,” says Lieb. “It was clearly a settlement that was occupied from the mid- to late 1400s through the early 1600s.” According to Mississippi State University archaeologist Tony Boudreaux, the sites at Stark Farm appear to confirm Spanish descriptions of Chikasha settlements, in which houses were dispersed across ridge tops rather than clustered together in large towns. “The Indigenous settlements they describe aren’t villages in the sense of houses bunched close together,” he says. “Instead, each house was built at a distance in sight of others in a very open environment.”

The greatest surprise came to light during extensive metal detecting surveys when archaeologists uncovered more than 80 iron, lead, and copper alloy artifacts. The Chikasha would not have had access to these raw materials at this time, so the items were conspicuously out of place. At first these objects appeared to be insignificant pieces of metal, but closer inspection revealed that they were actually pieces of sixteenth-century Spanish objects. “We could barely believe our eyes as the Spanish metal artifacts began to emerge,” Lieb says. The collection is now one of the largest assemblages of sixteenth-century metal items found anywhere in the southeastern United States.

The greatest surprise came to light during extensive metal detecting surveys when archaeologists uncovered more than 80 iron, lead, and copper alloy artifacts. The Chikasha would not have had access to these raw materials at this time, so the items were conspicuously out of place. At first these objects appeared to be insignificant pieces of metal, but closer inspection revealed that they were actually pieces of sixteenth-century Spanish objects. “We could barely believe our eyes as the Spanish metal artifacts began to emerge,” Lieb says. The collection is now one of the largest assemblages of sixteenth-century metal items found anywhere in the southeastern United States.

Although the metal is clearly European in origin, the objects themselves are typically Native American. They include an assortment of celts or adzes, cutting and scraping tools, and even decorative items called tinkler cones that were attached to clothing or worn in the hair. It appeared to the archaeologists that the Chikasha had somehow obtained an assortment of European objects, found very little use for them in their original state, and altered them to fit their needs. “The Chickasaw are not going to shoe a horse in 1541 in northeast Mississippi, so they say, ‘Let’s take this horseshoe and break it up into some blade tools that make more sense to us,’” says Boudreaux. Chain links, barrel bands, nails, and axes were subsequently ground down, bent, and transformed into Chikasha tools and pendants.

The glaring question facing archaeologists was how these European objects had ended up at Stark Farm in the first place. Had the site been closer to the coast, it might have been reasonable to assume that they were acquired through trade or presented as gifts by the Spanish, who had established a presence in Florida and around the Gulf of Mexico by the mid-1500s. Given their findspots in northeast Mississippi, this explanation was unlikely. Prior to the late 1600s, only one European expedition had traveled so deep into this region—the notorious and ill-fated Spanish mission of colonization, the de Soto entrada of 1539 to 1543.

The glaring question facing archaeologists was how these European objects had ended up at Stark Farm in the first place. Had the site been closer to the coast, it might have been reasonable to assume that they were acquired through trade or presented as gifts by the Spanish, who had established a presence in Florida and around the Gulf of Mexico by the mid-1500s. Given their findspots in northeast Mississippi, this explanation was unlikely. Prior to the late 1600s, only one European expedition had traveled so deep into this region—the notorious and ill-fated Spanish mission of colonization, the de Soto entrada of 1539 to 1543.

Cobb believes that all signs point to the metal artifacts at Stark Farm being directly or indirectly associated with the infamous Spanish expedition. “There are items, such as the medieval-style horseshoe fragments and barrel band fragments, that are highly characteristic of sixteenth-century Spanish entrada assemblages,” he says. “We know that there were no other Spanish expeditions in this location, and there are too many objects to be easily attributable to exchange into the interior at this point in time. That pretty much leaves us with de Soto.” If the Stark Farm material is indeed connected with de Soto, it was likely lost during his 1540–1541 encounter with the Chikasha, a fateful meeting that culminated in the Battle of Chikasha.

Cobb believes that all signs point to the metal artifacts at Stark Farm being directly or indirectly associated with the infamous Spanish expedition. “There are items, such as the medieval-style horseshoe fragments and barrel band fragments, that are highly characteristic of sixteenth-century Spanish entrada assemblages,” he says. “We know that there were no other Spanish expeditions in this location, and there are too many objects to be easily attributable to exchange into the interior at this point in time. That pretty much leaves us with de Soto.” If the Stark Farm material is indeed connected with de Soto, it was likely lost during his 1540–1541 encounter with the Chikasha, a fateful meeting that culminated in the Battle of Chikasha.

In December 1540, a band of Chikasha warriors stood on the banks of the Tombigbee River near present-day Columbus, Mississippi. On the opposing bluff was what had to be an almost unimaginable sight––a strange group of foreigners equipped with unfamiliar arms clad in metal armor and accompanied by peculiar animals such as horses, pigs, and dogs of war, the likes of which the Chikasha had never seen. The Europeans were the first white men the Chikasha had ever met. “These moments of contact would have just been extraordinary,” says Boudreaux. “Can you imagine what it must be like to meet a new kind of person that you had no idea existed? It’s hard to think of any analog in modern life.”

The Chikasha remained cautious yet steadfast. They were dressed for war and shouted across the river at the intruders, even firing arrows to warn the interlopers not to cross. By this point de Soto was accustomed to this type of greeting from Indigenous peoples and was not deterred. The conquistador was on his second year into his foray through the American Southeast, the first European to have ventured so far inland from the coast.

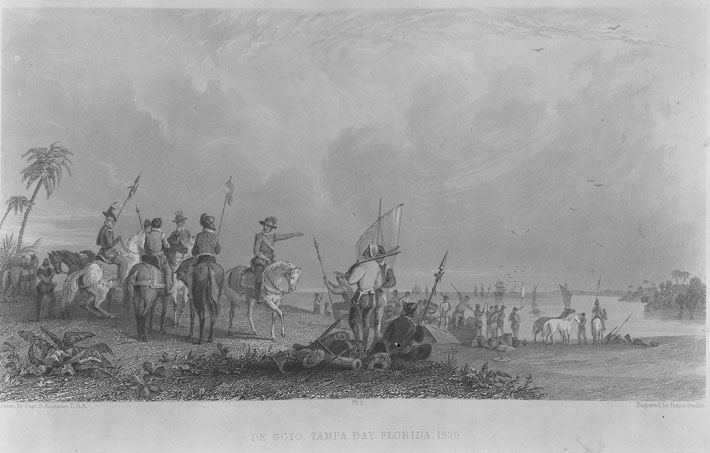

Although there is little hard evidence of his exact route, there are at least four contemporaneous written sources that provide details of the Spanish entrada. They record that de Soto landed near Tampa, Florida, in 1539 with around 700 men. The Spaniard had arrived in the New World as a young man and participated in the conquests of Panama and Nicaragua before becoming a captain under Francisco Pizarro during his subjugation of Peru. This episode made de Soto a very wealthy man, and an even more ambitious one. He then turned his sights on La Florida, land the Spanish had already laid claim to. “De Soto was seeking to establish a profitable colony in La Florida based on mineral wealth, slavery, and commerce similar to what he experienced earlier in Panama, Nicaragua, and Peru,” says Lieb. “He wanted to be a famous and wealthy conquistador like Pizarro.” After he landed in Florida, de Soto made his first winter camp at Anhaica, the capital of the Apalachee people, near Tallahassee. Anhaica is the only site that has been excavated that is widely accepted as having been a de Soto encampment. Stark Farm would be the second if definitive evidence could be found.

Although there is little hard evidence of his exact route, there are at least four contemporaneous written sources that provide details of the Spanish entrada. They record that de Soto landed near Tampa, Florida, in 1539 with around 700 men. The Spaniard had arrived in the New World as a young man and participated in the conquests of Panama and Nicaragua before becoming a captain under Francisco Pizarro during his subjugation of Peru. This episode made de Soto a very wealthy man, and an even more ambitious one. He then turned his sights on La Florida, land the Spanish had already laid claim to. “De Soto was seeking to establish a profitable colony in La Florida based on mineral wealth, slavery, and commerce similar to what he experienced earlier in Panama, Nicaragua, and Peru,” says Lieb. “He wanted to be a famous and wealthy conquistador like Pizarro.” After he landed in Florida, de Soto made his first winter camp at Anhaica, the capital of the Apalachee people, near Tallahassee. Anhaica is the only site that has been excavated that is widely accepted as having been a de Soto encampment. Stark Farm would be the second if definitive evidence could be found.

After departing Anhaica in the spring of 1540, the Spanish traipsed nearly 4,000 miles on a circuitous and meandering journey through the American Southeast. This included stops in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas. To his dismay, de Soto soon realized that this new territory was very different from the lands he had explored in South and Central America. There, he had encountered temples and cities full of gold, but the Native American communities of North America lacked such material wealth. Moreover, his custom of demanding food from his Indigenous hosts and forcing many men and women into servitude did not ingratiate him with the Native peoples he met. “The Spanish soon made themselves unwelcome almost everywhere they went,” Lieb says. In October of 1540, when de Soto was passing through Alabama, his men were ambushed by the powerful Native American leader Tuscalusa at a town called Mabila. De Soto’s army survived the melee, but he lost a tremendous amount of the supplies he needed to sustain his men, especially since winter was approaching. After limping away from Mabila, de Soto changed course and headed northwest to a place that he had been told was rich with an abundance of maize and other crops—Chikasha.

After departing Anhaica in the spring of 1540, the Spanish traipsed nearly 4,000 miles on a circuitous and meandering journey through the American Southeast. This included stops in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas. To his dismay, de Soto soon realized that this new territory was very different from the lands he had explored in South and Central America. There, he had encountered temples and cities full of gold, but the Native American communities of North America lacked such material wealth. Moreover, his custom of demanding food from his Indigenous hosts and forcing many men and women into servitude did not ingratiate him with the Native peoples he met. “The Spanish soon made themselves unwelcome almost everywhere they went,” Lieb says. In October of 1540, when de Soto was passing through Alabama, his men were ambushed by the powerful Native American leader Tuscalusa at a town called Mabila. De Soto’s army survived the melee, but he lost a tremendous amount of the supplies he needed to sustain his men, especially since winter was approaching. After limping away from Mabila, de Soto changed course and headed northwest to a place that he had been told was rich with an abundance of maize and other crops—Chikasha.

Word of the Spaniards’ exploits had likely reached the Chikasha prior to their arrival. In a strategic move, the Chikasha had abandoned a small village within their territory around 25 miles west of the Tombigbee River, which the Spanish also called Chikasha. De Soto planned to winter his troops in this small encampment, which contained around 20 houses. Sensing that allying with the Spanish was more beneficial to his people than being enemies, the Chikasha minko initially allowed the strangers to stay, even supplying them with food. “I think in evaluating the situation, he pondered how it could be used to his advantage and to the advantage of his people,” Boudreaux says. Yet it was an uneasy peace.

During the winter months of 1540 and 1541, as they had done time and again during their 18-month trek, the Spanish began to provoke their hosts. Following a dispute concerning stolen pigs, de Soto executed two Chikasha men and chopped off the hands of a third as a warning and a symbol of the Europeans’ authority. Mounting tensions reached a boiling point in the early spring of 1541 when De Soto insisted that the Chikasha supply him with 200 men and women to assist him on his journey into the unknown. “As the Spanish were preparing to move on, they demanded hundreds of tamemes, or ‘burden bearers,’” says Lieb. “They were basically slaves.” This was the last straw.

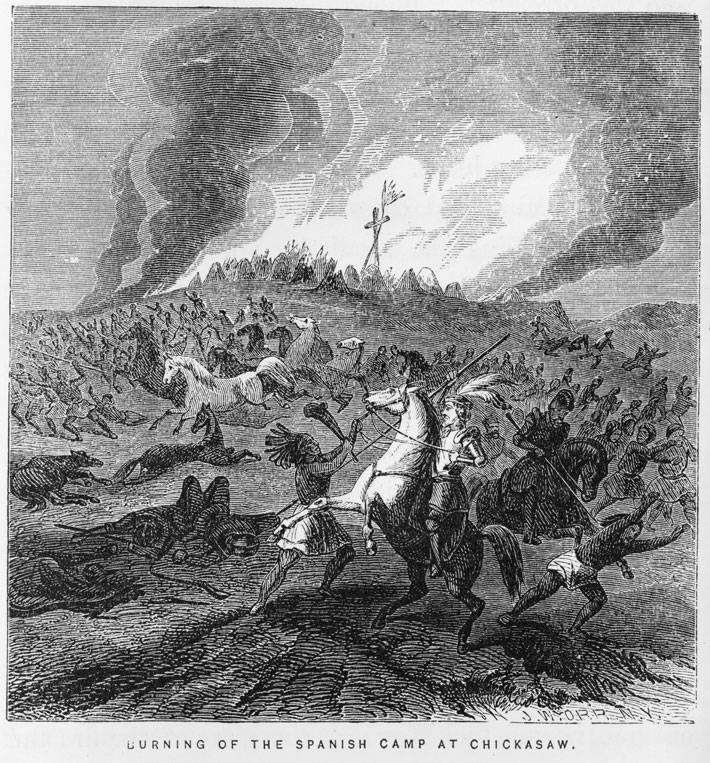

In the middle of the night in early March, hundreds of Chikasha warriors stormed the Spanish-occupied village, catching the sleeping Europeans by surprise. They set fire to the houses, killed between 10 and 15 Spaniards and injured almost all the others. Amid the chaos, de Soto himself was said to have been thrown from his horse. Just as quickly and silently as they had appeared, the Chikasha were gone—it was a Mississippian strategy to strike quickly, inflict damage upon their enemy, and retreat before losing any warriors. One firsthand Spanish account written by a man named Luys Hernández de Biedma questioned why they had been spared. “Without our resisting them or doing a thing, the Indians turned to flee and left us, because if they had pursued us, not a man of all of us would have escaped,” he wrote.

The Chikasha had made their message clear––although the Europeans had greater military technology, when it came to military valor, it was the Chikasha who reigned supreme. The battle still resonates throughout Chickasaw history today, nearly 500 years later. “I think that most Chickasaws consider the story of the Battle of Chikasha to be a point of pride,” says Lieb. “They were the only ones to have really whipped de Soto.” The Chikasha were already renowned for their military prowess and bravery among neighboring Native tribes, and after multiple encounters with early European colonists, records of the time began to refer to them as the “Spartans of the Lower Mississippi Valley.” “The warrior culture of the Chickasaw has been much ballyhooed, but it is indeed real,” says Lieb. “Primary accounts of the period repeat again and again the ferocity and achievements of Chickasaw warriors.”

The Chikasha had made their message clear––although the Europeans had greater military technology, when it came to military valor, it was the Chikasha who reigned supreme. The battle still resonates throughout Chickasaw history today, nearly 500 years later. “I think that most Chickasaws consider the story of the Battle of Chikasha to be a point of pride,” says Lieb. “They were the only ones to have really whipped de Soto.” The Chikasha were already renowned for their military prowess and bravery among neighboring Native tribes, and after multiple encounters with early European colonists, records of the time began to refer to them as the “Spartans of the Lower Mississippi Valley.” “The warrior culture of the Chickasaw has been much ballyhooed, but it is indeed real,” says Lieb. “Primary accounts of the period repeat again and again the ferocity and achievements of Chickasaw warriors.”

After regrouping, the decimated Spanish departed Chikasha territory. They would be the last Europeans to set foot there for almost 150 years. De Soto himself died a little over a year later, shortly after becoming the first European to cross the Mississippi River. His ragged and starving men, numbering about half of the 700 that they once were, turned around and headed back to Spanish territory in Mexico.

Is the collection of metal artifacts found at Stark Farm evidence of the Battle of Chikasha and proof of de Soto’s route through the area? There are some telltale signs of the Spanish military among the artifacts, including lead musket shot, a ramrod tip, a sword fragment, and a cannonball used for a swivel gun or a Spanish verso, a small type of cannon. And, a decorative medallion emblazoned with a gold cross was likely part of a horse bridle. “There are military aspects to the collection for which the de Soto entrada is the only explanation,” Lieb says.

The archaeologists remain cautious, however, about declaring that they have discovered the long-lost site of Chikasha. Eyewitness Spanish accounts describe how the village was burned and dozens of horses and pigs were caught in the conflagration. But, thus far, no evidence of extensive burning or any European animal remains have been found, although the excavation area has been limited. Nonetheless, the quantity of sixteenth-century metal artifacts strongly suggests that the Chikasha who inhabited Stark Farm 480 years ago lived in the vicinity of the Spanish encampment. It’s likely that after the smoke had cleared and the Spanish had departed, the Chikasha pored over the remnants of the Spanish camp collecting whatever had been left behind. The amount of Spanish material found at Stark Farm also could have come from small-scale trade between the Chikasha and Spanish soldiers over the winter, or items taken during the Battle of Chikasha. “I think most of our colleagues now concur that we are in the vicinity of Chikasha,” says Cobb, “if not on top of it.”

The transformation of the European objects into tools that better suited the Chikasha is evidence of their ability to adjust as the world around them began to irrevocably change, and the finds at Stark Farm have underscored the perseverance of the Chikasha way of life. Even though de Soto and his men crossed through their land, and they came face-to-face with the Spaniards, life within the Chikasha community seems to have continued as it had done before, something archaeologists did not expect. “I think we used to assume that maybe Native societies fell apart very quickly after the first Europeans passed through their lands because of violence and disease,” says Boudreaux. “But one thing we’re seeing archaeologically is that, at least in the short term, Native lifeways survive. We see a lot of continuity, a lot of persistence, which I don’t know that we would have really expected twenty or thirty years ago.”

The transformation of the European objects into tools that better suited the Chikasha is evidence of their ability to adjust as the world around them began to irrevocably change, and the finds at Stark Farm have underscored the perseverance of the Chikasha way of life. Even though de Soto and his men crossed through their land, and they came face-to-face with the Spaniards, life within the Chikasha community seems to have continued as it had done before, something archaeologists did not expect. “I think we used to assume that maybe Native societies fell apart very quickly after the first Europeans passed through their lands because of violence and disease,” says Boudreaux. “But one thing we’re seeing archaeologically is that, at least in the short term, Native lifeways survive. We see a lot of continuity, a lot of persistence, which I don’t know that we would have really expected twenty or thirty years ago.”

The Spaniards may have been the first Europeans to test the Chikasha’s mettle, but they were certainly not the last. In the coming centuries, two other growing colonial powers gradually encroached upon Chikasha territory—the French from the west and south, and the British from the east. As they did with the Spanish, their diplomatic tact and their skills in battle helped the Chikasha prosper at a time when other Native peoples in North America were quickly disappearing. “The Chickasaws survived the crushing colonial period because they were adaptable and played the seams between empires expertly,” says Lieb. “Rather than feeling squeezed, I think they thrived in playing the British and the French against each other.”

The Chikasha would again prove pivotal in the history of North America in 1736 when they repelled a French army attack on their settlements at Hikki’ya’, or Ackia, and Chokkilissa’, or Ogoula Tchetoka. Their defeat of the French ultimately set off a chain of events that helped lead to the British victory over France in the French and Indian War (1754–1763). This resulted in the French ceding their territories in North America and being expelled from the continent.

Ackia and Ogoula Tchetoka have also been recently identified and investigated by archaeologists. Along with Stark Farm, they are part of the growing number of confirmed Chickasaw ancestral sites in the Mississippi Blackland Prairie. These efforts are reconnecting the Chickasaw, and especially the younger generations, with their past and confirming long-held tribal beliefs. They are also proving why the unofficial motto of the Chickasaw Nation remains “Unconquered and Unconquerable.”

Jason Urbanus is a contributing editor at ARCHAEOLOGY.