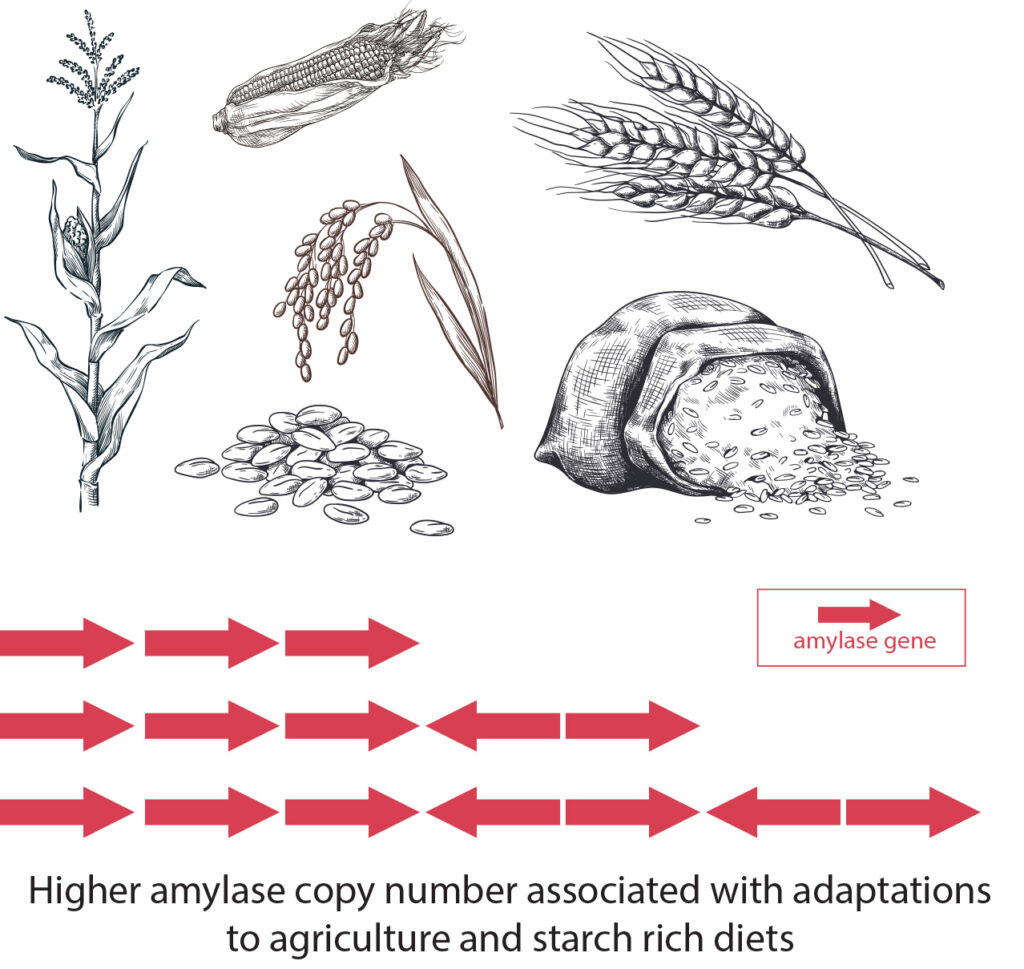

BUFFALO, NEW YORK—According to a report in The New York Times, two separate studies conducted by Omer Gokcumen of the University at Buffalo and Peter Sudmant of the University of California, Berkeley, suggest that hominins began producing more genes to produce amylase, an enzyme that begins digesting starches in the mouth, several hundred thousand years ago, and again some 12,000 years ago. Gokcumen thinks that the first change may be linked to the use of fire and cooking, which would have made starchy tubers more digestible. It has been thought that individuals who had more amylase in their saliva may have been able to absorb more nutrition, and therefore may have had an advantage over individuals with fewer copies of the genes. Mutations detected in some hunter-gatherer genes, however, indicate that amylase genes were lost over generations, and therefore likely did not confer any evolutionary advantage. Then around 12,000 years ago, as the farming of wheat, barley, and potatoes began, extra amylase genes have been found to have become more common among people who lived in Europe and Western Asia. Gokcumen now suggests that amylase in saliva may act as a signal to the body that food is on the way, prompting the production of insulin and the absorption of more sugar from starches in the diet. “If you have lots of bread around, there’s no problem,” Gokcumen said. “But if you’re just barely surviving, then I think it will be a matter of life and death,” he concluded. Read one of the original scholarly articles about this research in Nature. To read about a starchy spud that Native peoples of the American Southwest ate at least 10,000 years ago, go to “Letter from the Four Corners: In Search of Prehistoric Potatoes.”