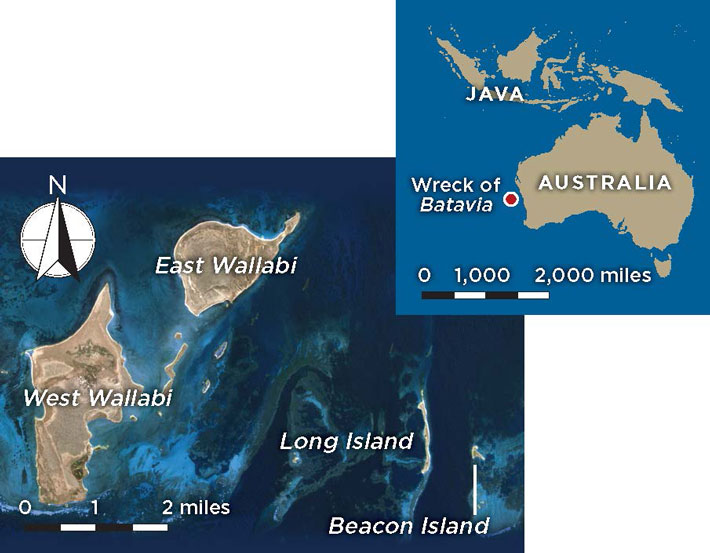

Treeless, almost uninhabited, buffeted by winds and ocean swells, the 100 islands and coral reefs known as the Houtman Abrolhos, off Australia’s west coast, is a hazard that sailors have tried to avoid for four centuries. The islands teem with sea lions, wallabies, lizards, and seabirds. Trawlers today ply the waters nearby to scoop up fish and lobster by the ton. Yet as scores of sea captains have learned the hard way, the archipelago’s coral reefs can rip the bottom off a wayward ship. Sitting as monuments to hubris, or at least carelessness, remains of a few of these wrecked vessels can still be seen shifting in the waves.

Treeless, almost uninhabited, buffeted by winds and ocean swells, the 100 islands and coral reefs known as the Houtman Abrolhos, off Australia’s west coast, is a hazard that sailors have tried to avoid for four centuries. The islands teem with sea lions, wallabies, lizards, and seabirds. Trawlers today ply the waters nearby to scoop up fish and lobster by the ton. Yet as scores of sea captains have learned the hard way, the archipelago’s coral reefs can rip the bottom off a wayward ship. Sitting as monuments to hubris, or at least carelessness, remains of a few of these wrecked vessels can still be seen shifting in the waves.

Before dawn on June 4, 1629, with just over 300 people aboard, the Dutch merchant ship Batavia struck a reef near the northern end of the archipelago, becoming the first known European vessel to meet its end on the Houtman Abrolhos. In the final weeks of a nine-month journey to the Dutch entrepot of Batavia, on Java, the ship carried 12 chests packed with silver coins and treasure that merchants of the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), or Dutch East India Company, planned to trade for the spices, porcelains, and silks coveted by Dutch burghers. The cargo was worth about 250,000 guilders, or about $15 million today. Wealthy, self-confident Holland was in the process of throwing off the rule of the Spanish Habsburgs, and of creating its own commercial empire, which already extended to the far side of the Indian Ocean.

Batavia did not sink immediately. She listed in the swells for nine days, her wooden hull slowly disintegrating, giving time for all on board—crewmen, cooks, soldiers, and passengers, of whom about 20 were women, mostly wives of VOC merchants or administrators—to flee on boats and flotsam to two tiny islands. A rash few tried to swim and drowned. Once ashore, the survivors faced the immediate problem of finding water. They had managed to bring a few barrels of fresh water with them, but, in the absence of rain, which was scarce on the islands, it would soon run out. The ship’s commander, a VOC official named Francisco Pelsaert, sailed in a 30-foot longboat with some officers and seamen over the horizon to the Australian continent, about 50 miles east, in search of water. But the South-Land, as it was known, was so poorly mapped that they had no idea where to look. They sailed north along the coast, putting ashore here and there to search for a spring or river. They glimpsed Aboriginal people, but were unable to engage with them as they fled whenever the foreign men approached. In desperation, Pelsaert opted to sail to Java, a journey of nearly 2,000 miles. Thirty days after the ship wrecked, Pelsaert and his crew reached Batavia.

Batavia did not sink immediately. She listed in the swells for nine days, her wooden hull slowly disintegrating, giving time for all on board—crewmen, cooks, soldiers, and passengers, of whom about 20 were women, mostly wives of VOC merchants or administrators—to flee on boats and flotsam to two tiny islands. A rash few tried to swim and drowned. Once ashore, the survivors faced the immediate problem of finding water. They had managed to bring a few barrels of fresh water with them, but, in the absence of rain, which was scarce on the islands, it would soon run out. The ship’s commander, a VOC official named Francisco Pelsaert, sailed in a 30-foot longboat with some officers and seamen over the horizon to the Australian continent, about 50 miles east, in search of water. But the South-Land, as it was known, was so poorly mapped that they had no idea where to look. They sailed north along the coast, putting ashore here and there to search for a spring or river. They glimpsed Aboriginal people, but were unable to engage with them as they fled whenever the foreign men approached. In desperation, Pelsaert opted to sail to Java, a journey of nearly 2,000 miles. Thirty days after the ship wrecked, Pelsaert and his crew reached Batavia.

On the islands where the survivors languished, meanwhile, horror ensued. A charismatic VOC merchant named Jeronimus Cornelisz was the highest-ranking authority in the absence of Pelsaert and the ship’s skipper, Ariaen Jacobsz. At first, everyone bowed to Cornelisz’s whims as a few dozen sailors and soldiers loyal to him commandeered the limited store of food and water. Within a few weeks, he began ordering his henchmen to kill those who were sick or dying, ostensibly to reduce the number of mouths that had to be fed. Soon they expanded their warrant to eliminate anyone who challenged their authority. During a month of terror, they bludgeoned or slit the throats of carpenters, craftsmen, rival sailors, and women who were too old or infirm to interest them sexually. They forced others onto boats and set them adrift or threw them into the sea to drown. They clubbed to death the wife of the ship’s preacher and seven of their eight children, leaving their oldest daughter to serve as a concubine to one of the killers. The preacher, Gijsbert Bastiaensz, later wrote a detailed, if slightly deranged, account of all he had witnessed.

On the islands where the survivors languished, meanwhile, horror ensued. A charismatic VOC merchant named Jeronimus Cornelisz was the highest-ranking authority in the absence of Pelsaert and the ship’s skipper, Ariaen Jacobsz. At first, everyone bowed to Cornelisz’s whims as a few dozen sailors and soldiers loyal to him commandeered the limited store of food and water. Within a few weeks, he began ordering his henchmen to kill those who were sick or dying, ostensibly to reduce the number of mouths that had to be fed. Soon they expanded their warrant to eliminate anyone who challenged their authority. During a month of terror, they bludgeoned or slit the throats of carpenters, craftsmen, rival sailors, and women who were too old or infirm to interest them sexually. They forced others onto boats and set them adrift or threw them into the sea to drown. They clubbed to death the wife of the ship’s preacher and seven of their eight children, leaving their oldest daughter to serve as a concubine to one of the killers. The preacher, Gijsbert Bastiaensz, later wrote a detailed, if slightly deranged, account of all he had witnessed.

One or two of Cornelisz’s gang descended from fallen aristocratic families, but most were working-class men from towns such as Groningen, Bremen, and Maastricht, hired by the VOC for their physical strength to guard the Dutch trading colony at Batavia against rivals and pirates. Empowered by their leader, to whom they signed an oath of loyalty, the men were soon murdering for fun and entertaining themselves with fantasies about how they would overrun any rescue ship that might come, go pirating, and retire rich in Spain.

![]() It took Pelsaert an additional two months to return on the ship Sardam, a tragic delay caused by a faulty initial reading of the position of the islands where the castaways were surviving on fish, seabirds, and sea lion blubber. Many had scurvy. When he arrived, he learned that Cornelisz and his gang had murdered about 115 people and were raping the surviving women. About 30 others had died of disease or neglect. Members of Cornelisz’s inner circle were parading about in bright red clothes with golden lace looted from the wreck. Cornelisz himself, however, had been taken prisoner. His campaign had inspired a mutiny led by a minor officer named Wiebbe Hayes who was encamped on the island of West Wallabi and was receiving refugees from Beacon Island, a seven-acre plot of sand and scrub where most of the survivors lived and where Cornelisz had his headquarters. When Cornelisz and his henchmen tried to invade West Wallabi, Hayes and his men killed four of them and took Cornelisz prisoner. Upon Pelsaert’s return, Hayes delivered Cornelisz bound and gagged to the commander, and the ordeal soon ended.

It took Pelsaert an additional two months to return on the ship Sardam, a tragic delay caused by a faulty initial reading of the position of the islands where the castaways were surviving on fish, seabirds, and sea lion blubber. Many had scurvy. When he arrived, he learned that Cornelisz and his gang had murdered about 115 people and were raping the surviving women. About 30 others had died of disease or neglect. Members of Cornelisz’s inner circle were parading about in bright red clothes with golden lace looted from the wreck. Cornelisz himself, however, had been taken prisoner. His campaign had inspired a mutiny led by a minor officer named Wiebbe Hayes who was encamped on the island of West Wallabi and was receiving refugees from Beacon Island, a seven-acre plot of sand and scrub where most of the survivors lived and where Cornelisz had his headquarters. When Cornelisz and his henchmen tried to invade West Wallabi, Hayes and his men killed four of them and took Cornelisz prisoner. Upon Pelsaert’s return, Hayes delivered Cornelisz bound and gagged to the commander, and the ordeal soon ended.

Batavia’s saga became a sensation in Europe, recounted in a 1645 book called The Unlucky Voyage of the Batavia, which was based mainly on Pelsaert’s log and confessions from the renegades and survivors’ accounts recorded by him. Among Australians, the story has been told and retold as a kind of alternative national foundation myth in books, films, and even an opera, a tale of fear and endurance revealing how the first Europeans to encounter Australia saw it merely as an obstacle to their trading ambitions and a place that brought out the worst human instincts.

Divers located the wreck of Batavia 20 feet underwater in 1963. Between 1971 and 1976, researchers from the Western Australian Museum (WAM) salvaged the wreck, reconstructed its hull, and retrieved 26,700 artifacts, the largest maritime archaeological recovery in Australia’s history. Now archaeologists are excavating the islands where Batavia’s survivors camped and are finding bones and artifacts that point to the lot of travelers clinging to habits from home with no idea whether they would ever be rescued—while trying to save themselves from a psychopathic tyrant. They are also unearthing numerous skeletons, a few of which have horrific head wounds. While reconstructing the survivors’ story, archaeologists are documenting the spread of Dutch material culture, which, for the first time, had reached Australia. “We are finding a living surface, the cultural remains that people used during the three months they were marooned,” says Corioli Souter, a WAM archaeologist and curator. “It’s not the goal, but we are also pulling up quite a few bodies.”

Divers located the wreck of Batavia 20 feet underwater in 1963. Between 1971 and 1976, researchers from the Western Australian Museum (WAM) salvaged the wreck, reconstructed its hull, and retrieved 26,700 artifacts, the largest maritime archaeological recovery in Australia’s history. Now archaeologists are excavating the islands where Batavia’s survivors camped and are finding bones and artifacts that point to the lot of travelers clinging to habits from home with no idea whether they would ever be rescued—while trying to save themselves from a psychopathic tyrant. They are also unearthing numerous skeletons, a few of which have horrific head wounds. While reconstructing the survivors’ story, archaeologists are documenting the spread of Dutch material culture, which, for the first time, had reached Australia. “We are finding a living surface, the cultural remains that people used during the three months they were marooned,” says Corioli Souter, a WAM archaeologist and curator. “It’s not the goal, but we are also pulling up quite a few bodies.”

Named for an ancient Germanic tribe whom the Dutch considered their ancestors, Batavia sailed on her maiden voyage from Texel, Holland, on October 29, 1628, as the flagship of a fleet of seven vessels heading to the East Indies. Along with Pelsaert, aboard ship was her skipper, Jacobsz. After a long stopover at the Cape of Good Hope, a power struggle erupted after Pelsaert publicly disciplined the more experienced Jacobsz for drunkenness. Pelsaert had doubts about Jacobsz’s competence, and the skipper enlisted the help of the future murderer Cornelisz and other officers to plot a mutiny—which they might have carried out, if not for the shipwreck.

Batavia’s demise came about in part because of a radical shift in navigation routes in the early 1600s that allowed ships to reach the East Indies faster. This shift had also led to the accidental European discovery of Australia. Following the time-honored route sailed by the Portuguese beginning in the 1400s, European ships bound for Asia sailed south around Africa, then north along the continent’s east coast and then east across the Indian Ocean. But that route had fallen out of favor because of its unreliable winds, stifling heat, and dangerous reefs. Around 1600, sea captains learned that it was faster to sail straight east from the southern tip of Africa at a latitude of around 35 degrees south for several weeks, and then turn north.

Batavia’s demise came about in part because of a radical shift in navigation routes in the early 1600s that allowed ships to reach the East Indies faster. This shift had also led to the accidental European discovery of Australia. Following the time-honored route sailed by the Portuguese beginning in the 1400s, European ships bound for Asia sailed south around Africa, then north along the continent’s east coast and then east across the Indian Ocean. But that route had fallen out of favor because of its unreliable winds, stifling heat, and dangerous reefs. Around 1600, sea captains learned that it was faster to sail straight east from the southern tip of Africa at a latitude of around 35 degrees south for several weeks, and then turn north.

That route carried its own dangers, however, as ships could easily sail too far east before turning north. This was how Europeans first encountered western Australia, starting with Dutch skipper Dirk Hartog, who landed at Shark Bay in 1616. Another Dutch captain, Willem Janszoon, had ventured south from New Guinea and hit the northern tip of Queensland in 1605, the first documented European contact with Australia. Three years later, Frederick de Houtman sailed up the Australian west coast and nearly struck reefs that he named the Houtman Abrolhos, abrolhos being a Portuguese word for reefs that he may have learned while sailing in Brazil. At no point did any of these early merchant-explorers see Australia as a place worth interacting with, much less settling. Yet the Dutch considered it theirs, if only by default; by 1648 it appeared on Dutch maps as “New Holland.”

Following de Houtman’s route, Batavia’s skipper was on deck when the ship crashed at full speed into the reef. What ensued was a chaotic scene of drunk sailors and terrified passengers struggling to abandon ship as the lower holds filled with water. “Our goodwill and diligence were impeded by the godless, unruly soldiers and sailors, and their likes, whom I could not keep out of the hold on account of the liquor or wine,” reported Pelsaert. Within a day of the wreck, they had managed to put ashore “180 souls, 20 casks of bread, and some small barrels of water” as well as “a casket of jewels.”

Following de Houtman’s route, Batavia’s skipper was on deck when the ship crashed at full speed into the reef. What ensued was a chaotic scene of drunk sailors and terrified passengers struggling to abandon ship as the lower holds filled with water. “Our goodwill and diligence were impeded by the godless, unruly soldiers and sailors, and their likes, whom I could not keep out of the hold on account of the liquor or wine,” reported Pelsaert. Within a day of the wreck, they had managed to put ashore “180 souls, 20 casks of bread, and some small barrels of water” as well as “a casket of jewels.”

Three months later, when he returned from Java, Pelsaert brought divers to salvage treasures he had been unable to remove from the ship. At some point he retrieved possibly the most valuable relic of all, a fourth-century A.D. artifact known as the Constantine cameo. Depicting Roman deities and mythological centaurs in delicately carved agate, the jewel-encrusted piece had been marked for sale to the Mughal emperor of India on behalf of an Amsterdam jeweler. When Pelsaert finally got the cameo to Java, and then to India, the emperor had died, and his successor had no interest in European baubles. The Constantine cameo wound up back in Europe, another disappointment for Batavia’s unlucky commander.

Pelsaert’s divers must have worked diligently. Although archaeologists led by Jeremy Green, head of maritime archaeology at WAM, found 10,600 coins and a silver ewer, they recovered relatively few precious objects from the wreck site. Instead, scuba teams retrieved troves of humble artifacts that speak of life in Holland and that surely reminded passengers of home. They recovered an inkwell, a fountain pen, and scores of glass bottles that would have carried ointments or perfumes. Other objects hinted at how passengers and crew may have passed the time on a long sea journey: chess pieces made of bone, parts of a trumpet, and hundreds of “Beardman” jugs, stoneware vessels each decorated with a distinctive hirsute face and three medallions representing part of the coat of arms of Amsterdam.

Pelsaert’s divers must have worked diligently. Although archaeologists led by Jeremy Green, head of maritime archaeology at WAM, found 10,600 coins and a silver ewer, they recovered relatively few precious objects from the wreck site. Instead, scuba teams retrieved troves of humble artifacts that speak of life in Holland and that surely reminded passengers of home. They recovered an inkwell, a fountain pen, and scores of glass bottles that would have carried ointments or perfumes. Other objects hinted at how passengers and crew may have passed the time on a long sea journey: chess pieces made of bone, parts of a trumpet, and hundreds of “Beardman” jugs, stoneware vessels each decorated with a distinctive hirsute face and three medallions representing part of the coat of arms of Amsterdam.

The divers also recovered a surgeon’s bowl, easily identified by an indentation where male patients could place their neck for a shave—surgeons doubled as barbers. The bowl probably belonged to the ship’s surgeon, Frans Jansz, whose popularity with the crew may have led to his doom. After the wreck, four of Cornelisz’s henchmen murdered Jansz, whacking him on the head with a spiked club known as a morning star until he “was so hacked and stabbed,” according to one of Pelsaert’s witnesses.

The divers also recovered a surgeon’s bowl, easily identified by an indentation where male patients could place their neck for a shave—surgeons doubled as barbers. The bowl probably belonged to the ship’s surgeon, Frans Jansz, whose popularity with the crew may have led to his doom. After the wreck, four of Cornelisz’s henchmen murdered Jansz, whacking him on the head with a spiked club known as a morning star until he “was so hacked and stabbed,” according to one of Pelsaert’s witnesses.

Other finds show how the Dutch hoped to assert their presence in the East Indies and build prestige at the expense of rivals such as Britain. Green and his divers found 137 sandstone blocks, one emblazoned with the VOC symbol, which were intended for a portico that would span the entrance to the Castle of Batavia, the new headquarters of the company’s trading empire in Asia. The grand neoclassical structure would have towered over the castle gateway and now stands, fully assembled by staff in the 1980s, at WAM’s branch museum in the town of Geraldton. The divers also retrieved 28 cannons, one of which now sits in the arrivals lounge of Geraldton’s airport. Yet the most important find, says Green, was the ship itself. After they pulled up the stern and sides with a crane, he could see that caulking material made of tar and animal hair had survived between many of the hull’s perfectly fitted planks. Handsaw and adze marks were still visible. “It took two years just to build one of these ships, from selecting the timber in the forest to launching it,” says Green. “They were enormous investments, as significant as the money they were carrying.”

Fewer objects have been recovered on the islands, in part because Pelsaert’s salvage teams did a thorough job of scouring the survivors’ campsites, says Alistair Paterson of the University of Western Australia, lead archaeologist on the land sites. After musket-bearing soldiers from Sardam crushed the last throes of Cornelisz’s revolt, Pelsaert wrote that “the first thing I did was to seek the scattered jewels. These were all found, except a ring and a gold chain”—and he later found the ring. “The salvaging they did on the islands was quite exacting, and that would have been to prevent punishment by the VOC,” says Paterson. “It was a pretty ruthless company to work for. I think this is part of why we’re not finding more campsite materials. They swept up every last thimble.” Recovery efforts have been hindered by the fact that the soil on Beacon Island is made up mainly of loose coral, through which objects often drop as archaeologists try to excavate them. Burrowing seabirds have also pockmarked the island’s surface. “It’s a really poor site for survival of materials,” says Paterson.

Fewer objects have been recovered on the islands, in part because Pelsaert’s salvage teams did a thorough job of scouring the survivors’ campsites, says Alistair Paterson of the University of Western Australia, lead archaeologist on the land sites. After musket-bearing soldiers from Sardam crushed the last throes of Cornelisz’s revolt, Pelsaert wrote that “the first thing I did was to seek the scattered jewels. These were all found, except a ring and a gold chain”—and he later found the ring. “The salvaging they did on the islands was quite exacting, and that would have been to prevent punishment by the VOC,” says Paterson. “It was a pretty ruthless company to work for. I think this is part of why we’re not finding more campsite materials. They swept up every last thimble.” Recovery efforts have been hindered by the fact that the soil on Beacon Island is made up mainly of loose coral, through which objects often drop as archaeologists try to excavate them. Burrowing seabirds have also pockmarked the island’s surface. “It’s a really poor site for survival of materials,” says Paterson.

Archaeologists digging on Beacon Island have so far found a fine-toothed comb, a game token, amber beads, ceramic fragments, a spoon, and the rim of a trumpet horn inscribed with the name of its manufacturer and the year 1628 in Roman numerals. They have also uncovered the clasps of a book cover, probably from a Bible. Along with these quotidian objects, the 21 skeletons thus far excavated offer grim corroboration of Pelsaert’s written accounts. Seven bodies were found thrown haphazardly into a mass grave. One skull was missing a piece that had been smashed away, and another, that of a young female, had a cut mark that may not have been fatal, but was certainly delivered by a blade.

Excavations on West Wallabi Island, where the minor officer Hayes held out against Cornelisz, uncovered more everyday Dutch objects including book bindings, bits of clothing and lace, and crumpled pieces of lead. The most significant surviving trace of Hayes and his group of about 40 followers, however, is a two-room stone shelter they erected on the island’s eastern shore. It is the oldest European building in Australia. A second, smaller stone structure nearby may also have been built by Hayes’ people. That building stands next to West Wallabi’s only reliable source of fresh water, a rain catchment pool that Hayes and his men must have been overjoyed to find. After the wreck, Pelsaert had searched West Wallabi for water but missed the pool, given up, and headed to the mainland.

Before he left the island, Pelsaert noticed something very strange. “On these islands,” he wrote, “there are large numbers of cats, which are creatures of miraculous form, as big as a hare…the forepaws are very short, about a finger long.…The females have a pouch…where…their young grow.” He was, of course, describing wallabies—more precisely tammar wallabies—descendants of animals stranded on a few islands of the Houtman Abrolhos when sea levels rose at the end of the last Ice Age, 12,000 years ago. Pelsaert’s is the first written description of an Australian marsupial.

Before he left the island, Pelsaert noticed something very strange. “On these islands,” he wrote, “there are large numbers of cats, which are creatures of miraculous form, as big as a hare…the forepaws are very short, about a finger long.…The females have a pouch…where…their young grow.” He was, of course, describing wallabies—more precisely tammar wallabies—descendants of animals stranded on a few islands of the Houtman Abrolhos when sea levels rose at the end of the last Ice Age, 12,000 years ago. Pelsaert’s is the first written description of an Australian marsupial.

Descriptions of the islands’ curious wildlife offer the only relief from Pelsaert’s otherwise unremittingly bleak account of terror and retribution. “A man does a lot to stay alive,” he wrote wistfully, on why so many bowed to Cornelisz’s coercion. Lying between Beacon and West Wallabi, Long Island is a sandy spit where Batavia’s survivors went to hunt sea lions. One of the early massacres took place there, and archaeologists found a likely remnant of the event: a lead-and-iron morning star used to club people in the head. Once they had reestablished control, Pelsaert and his crew used timbers from the ship to build a gallows on Long Island and hanged Cornelisz and six of his accomplices. Six more were later executed in Batavia.

Paterson ran a metal detector all over Long Island. He found hundreds of corroded iron nails, rivets, and fastenings concentrated on a small rise on the part of the island closest to Beacon Island. The fragments include a wrought iron bolt of a type commonly forged in seventeenth-century Holland. Using chemical analysis, researchers have dated it to earlier than 1840, suggesting it was part of the gallows, Paterson says. Yet he does not expect to find human remains. The bodies were probably left swinging in the wind, as was the custom for criminals in Holland.

The final chapter of Batavia’s accidental encounter with Australia started with a reprieve. Pelsaert, according to his log, spared the lives of two of Cornelisz’s most hardened killers, a soldier named Wouter Loos, who had participated in the murder of the preacher’s family, and a boy of about 16 named Jan Pelgrom. Instead of executing them, he marooned them on the coast of mainland Australia, near the modern village of Kalbarri, with instructions to “make themselves known to the folk of this land by tokens of friendship.” He gave them knives, beads, bells, and mirrors with which to win the favor of the Aboriginal peoples living there. Pelsaert instructed Loos and Pelgrom that, “having become known to them, if they will take you into their villages to their chief men, have courage to go with them willingly. Man’s luck is found in strange places, [and]…because they have never seen white men, they will offer all friendship.” A pair of reprieved criminals became, in effect, the first white settlers in Australia. They were never heard from again. But their marooning uncannily foreshadowed the arrival of shiploads of British convicts starting in 1787. This was the first wave of European settlers and the beginning of modern Australia.

Roger Atwood is a contributing editor at ARCHAEOLOGY. To see more images, click here.